... and the River

This post includes how the land evolved through time; how mother nature did Chicago a favor; the original inhabiants; the Europeans that reached are shores; the cemeteries that influenced Lake View's developement; and the house that became a 'signature' hotel.

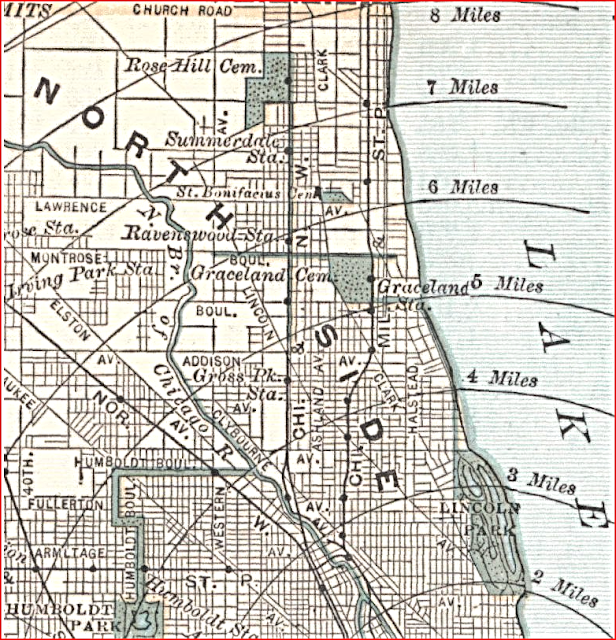

map - HathTrust.org

Read an extensive history on the era

map - Dearborn Magazine in 1922

About 14 thousand years ago during the tail end of the

last ice age the area of Lake View Township was under water.

Over three hundred million years ago our area of Illinois was covered with wetlands such as coastal swamps, deltas, and upland forests situated along an estuary bay and probably a much wider Chicago River. - Chicago History Museum

image - Illinois State Geological Survey

‘Illinois can boast a significant number of amphibians

and invertebrates dating to the Paleozoic Era (541,000,000 BC to

251,900,000), as well as a handful of Pleistocene periods (2,600,00 BC to

12,000 BC) pachyderms (Woolly Mammoths, Mastodons and other elephant type

mammals). For much of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic Eras (250,000,000 BC to

2,000,000 BC), Illinois was geologically unproductive in that period hence the lack of

fossils dating from this vast expanse of time. However, conditions improved

tremendously during the Pleistocene period when herds of Woolly Mammoths and

American Mastodons tramped across this state's endless plains (and left

scattered fossil remains to be discovered, piecemeal, by 19th & 20th-century

paleontologists).

image - Illinois State Geological Survey

Joe Devera, has been a geologist with the Illinois State

Geological Survey for over 30 years. "Other dinosaurs, such as T-Rex,

could be found in Illinois covered up by vegetation and soil.”’ - The Digital Research Library of Illinois

The Modern Era

The Chicago River flowed into Lake Michigan before 1900

In more ancient recent times, Lake Chicago also known as the Glacial Lake Chicago; term used by geologists for a lake that preceded Lake Michigan; was formed when the Wisconsin glacier retreated from the Chicago area, beginning about 14,000 years ago. Lake Chicago`s level, at its highest, was almost 60 feet higher than the level of present Lake Michigan and the lake completely covered the area now occupied by Chicago. Its northern outlet into the St. Lawrence River was still blocked by remnants of the glacier and it drained through the so-called Chicago outlet, a notch in the Valparaiso moraine, into the Mississippi system. Its western shores reached to where Oak Park and La Grange now exist. "The region destined to be covered by metropolitan Chicago took natural form following the retreat of the North American ice cap 10,000 years ago. Meltwaters from the glacier's Lake Michigan Lobe, pent up for a time behind morainic ridges deposited at the ice sheet's margins, formed glacial Lake Chicago and drained southwestward, scouring what is today the lower Des Plaines valley. As ice receded and water drained away, Lake Michigan remained behind, contained within its modern shoreline. The area straddles what turned out to be a permanent low-lying continental drainage divide between the basins of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. The numerous lakes and marshes of the region represent the retreating glacier's messy legacy. By the early nineteenth century a tall-grass prairie environment covered much of the area, with thin strips of forest colonizing sandy beach ridges and shallow valley bluffs."Author: Michael P. Conzen

Source: Newberry Library

The People

Who Settled Here:

The Originals

Tribes were more nomadic so did not believe in the tradition border locations like the European settlers would preferred.

Native Americans did not have set borders but moved around for hunting and agricultural survival. The Europeans did not quit understand this cultural difference.

Native American tribes in the United States are typically

divided into 8 distinct regions, within which tribes had some similarities

across culture, language, religion, customs and politics.

Northwest Coast

– Native Americans here had no need to farm as edible plants and animals were

plentiful in the land and sea. They are known for their totem poles, canoes

that could hold up to 50 people, and houses made of cedar planks.

California –

Over 100 Native American tribes once lived there. They fished, hunted small

game, and gathered acorns, which were pounded into a mushy meal.

The Plateau -

The Plateau Native Americans lived in the area between Cascade Mountains and

the Rocky Mountains. To protect themselves from the cold weather, many built

homes that were partly underground.

The Great Basin

– Stretching across Nevada, Utah, and Colorado, the Native Americans of the

Great Basin had to endure a hot and dry climate and had to dig for a lot of

their food. They were one of the last groups to have contact with Europeans.

The Southwest

– The Natives of the Southwest created tiered homes made out of adobe bricks.

Many of the tribes had skilled farmers, grew crops, and created irrigation

canals. Famous tribes here include the Navajo Nation, the Apache, and the

Pueblo Indians.

Northeast -

The Native Americans of the Northeast lived in an area rich in rivers and

forests. Some groups were constantly on the move while others built permanent

homes.

The Plains –

The Great Plains Indians were known for hunting bison, buffalo and antelope,

which provided abundant food. They were nomadic people who lived in teepees and

they moved constantly following the herds. - Ancient Originals

Map below

by Vincenzo Coronelli mid 1690's

A 1688 Map listing Chicago

zoomed belowzoomed more belowtext below - Chicagology/Facebook 'Over the course of four distinct periods of glacial melting, stretching as far back as 14,500 years ago, Chicago’s terrain was shaped by the ebbs and flows of melting ice. Through the process of littoral drift, where small bits of sand and organic matter drifted from place to place on the tide, small but distinct ridges were etched into the land. Those natural high grounds, rising no more than 10 or 15 feet above the rest of the terrain, became some of the pathways used by Native peoples as they began to inhabit the area about 11,000 years ago.These high points held obvious value: most of the land was swampy, and very little stayed dry year-round. Indigenous tribes passed down their understanding of the land’s natural features through oral traditions. Incoming European settlers, including French trappers traveling to the area during the 17th and 18th centuries, depended on this knowledge for survival. They also quickly came to understand the significance of the trails, adapting them for commercial and military purposes.'

a zoomed view below with a settlement

by in the area of Clark, Diversey, Broadway

zoomed even further ...

(red line should be Clark Street)

DNAinfo article

In 2013 artifacts were discovered within the City of Chicago at Rosehill Cemetery

WEST RIDGE — Ancient artifacts from an

"enormous" Native American settlement were uncovered along a gravel

and sand ridge that passes through the land that is soon to become a city park

near Rosehill Cemetery, officials said. Phil Millhouse, an archeologist with

the Illinois Archeological Survey, said he and his colleagues performed

"shovel tests" on the site earlier this year when they came across

fragments of arrow points, knives, ceramics and possibly a cooking kit. "It turned out there was a very large prehistoric

village on that ridge of sand and gravel that runs off the lake," he said.

The "enormous" site surrounded by wetlands had been occupied possibly

thousands of years before Europeans settled the area.

image via Calumet 412

The above image shows (Evanston Road) Broadway and north of Lawrence Avenue indicates Clark Street as a high ridge path

early 19th century. Almost all of the mounds in the Chicago area were lost due to development and the lack of understanding of this cultural importance of the indigenous peoples of our area.

This illustration is an example of the markers or landmarks that Native Americans nurtured, more than likely indicate direction or some sort of sign language. Settlers simply called them 'Indian Tree'.

by WBEZ Chicago

an extensive & well researched article

The Native American burial mound apparently was once located between Oakdale & Wellington east of Sheffield according to this article by WBEZ

"Early settlers destroyed hundreds if not thousands of

ancient sculptures, along with the historical record. They plowed under mounds

to farm the land or leveled them and built homes on the sites. In some cases,

early settlers claimed to have asked local Native Americans about the origins

of the mounds without receiving a clear answer. John Low, a Potawatomi Indian

and professor of American Indian studies, says he’s suspicious of these

accounts given that they took place during a power struggle over land. “[The

Natives] may have said that because they aren’t going to share with people,

[who] they regard as the enemy, the special-ness they know about a site.”

- Read more from the above title link.

The Native American Tribes

& U.S. Territories in 1812

a zoomed view below

by Chief Pokagon

28 pages & published in 1893

selected pages below

Who Next Settled Here:

Those Europeans

first came the Spanish, French, and then the English

map - Wikipedia

map -Vikings - Norman Descendants

map above - Wikipedia

map below - GeoCurrents

Early History

of Illinois Region

by Historical Review of Chicago & Cook County

Rendering of Chicago 1779 that features

the first non-native to settle - Jean Baptiste De Sable

British territory as of 1775 that included

the Northwest territories in 'sky blue in color'

interactive image - Accessible Archives-Facebook

at one period in time our area belonged to Connecticut

below is a 1771 map from Ebay

established after the Revolutionary War

once British territory as well that include Illinois

image - University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

a zoomed view below

The United States by 1818

Illinois earned statehood that year

the nation would expand westward as shown below

Henry Charles Carey & Isaac Lea Map

The establishment of the counties along the rivers came first due only economical transportation route at the time - rivers

Cook County was not established at this time

let alone a Lake View Township within it

images - Geography of Illinois by H O Lathrop (1940)

The Chicago Region

The colonists cometh

by Historical Review of Chicago & Cook County

image - Chicago in Maps by Robert A Holland

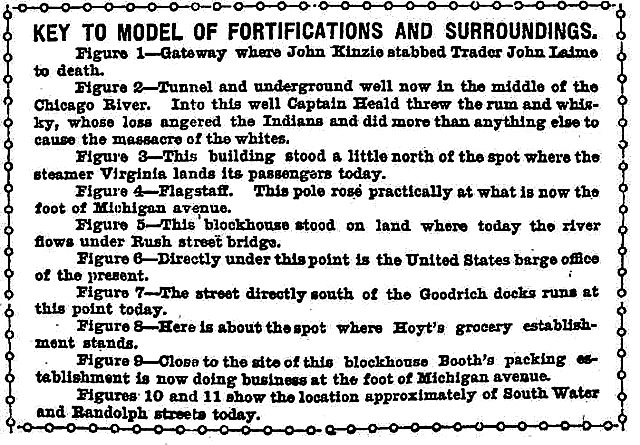

Fort Dearborn - Chicago - 1812

A Fort before Dearborn?

by Historical Review of Chicago & Cook County

map via Paul Petraitis-Facebook

top right along the river was the fort

from Kenneth Swedroe via Original Chicago-Facebook

images - The Digital Research Library of the Illinois

History Journal

Alfred Sully Depiction of the Fort

and another location

read the text below

via Windy City Historians/Facebook

Land of Forests

image - Chicago: growth of a metropolis

with a zoomed view south of Fullerton Avenue at the top

... a lot of trees & brush

both postcards - Ebay

mouth of Chicago River - from Card Cow

zoomed north of river indicated forest

Green Bay Road is Clark Street

a 1832 view

Chicago History Museum Collection via Paul Petraitis, Forgotten Chicago-Facebook

a 1853 view - Michael Thomas

via Forgotten Chicago-Facebook

1830 map - via Chicago Past

another view more detail 1830

photo - via Patrick McBriarty Windy City Historians-Facebook

This hand drawn map was created

by the Commander of Fort Dearborn.

1818 Matthew Carey's Potawatomi map

image - Early Chicago.com.

The Territory of Illinois became a State of the

Settlers vs Natives

The years 1832 & 1834 mark the end

of Native Americans east of the Mississippi

an article from 1832

Anthony Finley Map David Rumsey Map Collection 1831

Town of Chicago 1832 - Calumet 412

mouth of the Chicago River

image - Ebay

Treaty of Chicago of 1833 was the end of influence and the end of most hunting grounds for Native American tribes along the greater Great Lakes region. The United States drafted this treaty with the several villages of Potawatomi in Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Two years later a charter was granted by an early illustration - Ebay

Northeastern Illinois was again colonized by settlers from the United States beginning in the 1830's following the survey and sale of Canal Lands within the canal corridor to private interests. This enormous planned development by the federal govenment meant jobs for courageous easterners willing to move out of the 'comfort zones' to terrific terrian. 'In 1833, Congress appropriated funds to improve the harbor and construct piers to fortify the channel. The investment opened the river for larger ships and increased Chicago’s standing as a center for cross-continental trade.' Read this comprehesive article

image - Imgur

Henry S Tanner Map David Rumsey Map Collection 1836

Chicago, if not Lake View Township

"The streets of the village in the fall soon became deluged with mud. It lay in many places half a leg deep, up to the hubs of the carts and wagons, in the middle of the streets, and the only sidewalk we had was a single plank stretched from one building to another. The smaller scholars I used to bring to school and take home on my back, not daring to trust them on the slippery plank. One day I made a misstep and went down into the thick mire with a little one in my arms. With difficulty I regained my foothold, with both overshoes sucked off by this thick, slimy mud, which I never recovered."

- G. Sproat June 1887

Chief Waubonsie of the Pottowatomis

‘In 1835, [Chief] Waubonsie, then more than 70 years old,

traveled to Washington, D. C. to meet with delegations from other tribes. Waubonsie had an audience with President

Andrew Jackson and addressed him as "Brother-Brave." Nothing of any great importance was accomplished

with this visit. In 1837 all the Indians were rounded up and sent to

Chicago. There, they met other bands of

Pottawatomie from Michigan and Indiana, and began a harrowing walk to Missouri

and Kansas that later became known as the

image - Wikipedia

The last Native American area was located in the Evanston Township area know as Ouilmette according to Evanston History Center. "The Ouilmettes built a cabin for their family of eight children at Lake Street and Lake Michigan in what is now Wilmette (named for them, though the spelling was changed). Their home was a well-known stopping place for traders and travelers, and their farm continued to supply the growing settlement in Chicago. Archange and Antoine lived on the reservation until about 1838 when they joined fellow Potawatomi that had been removed to Council Bluffs, Iowa. It was there that Archange died in 1840 and Antoine in 1841. In 1844 their heirs petitioned the U.S. Government to sell the reservation’s land. The government purchased the land (640 acres) for $1,000 and then gradually re-sold it to real estate developers."

“Early Chicagoans, like most Americans in the 19th

century, were brutal pragmatists. They valued progress at any cost. In 1835,

city dwellers shed few tears over the scattering of the area’s original

inhabitants, the Potawatomi, despite the Potawatomi’s own lamentations—800

warriors marched across Chicago’s early wooden bridges in a ceremonial leaving

of the lakeshore. Their native fishing and hunting grounds having been over-taken,

they’d accepted a brokered agreement to move beyond the Mississippi River into

what is now Iowa. It was a deal they couldn’t refuse.”

The University of Chicago map illustration above indicated established subdivisions between 1844-1862. It is to be noted that this map was drafted in 1933 (so no Lincoln Park at the time), Sheridan Road proposed extension, and the rail lines were added to help the viewer with geography.

Land values assessment per square mile as of 1873-79 years after the incorporation of Lake View Township and 16 years before the annexation to Chicago.

A 1879 Encyclopedia map (to be zoomed) show streets and communities in Lake View Township such as Pine Grove, Andersonville, Ravenswood, Bowmanville, and a community called Henry Town. Also shown are the cemeteries of Rosehill & Graceland. Also, during this time period community of Rogers Park had earned its' distinction as a township seceding from Evanston Township. The Then Existing

Shores

The shoreline - pre development

postcards - Ebay

and another typical shoreline in 1903

photo - UIC via Explore Chicago Collection

Maps of the Shoreline

in 1894

1894 Sanborn Fire Map the shoreline consisted of street-end beaches; a time before Sheridan Road and the northward landfill & expansion of the park

A Place

to Sleep, Drink, & Party

along with shed for your horses

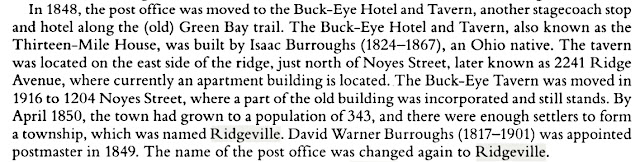

one of the first tavern hotels of the old township

image - 'Challenging Chicago' by Katy Crowley

Sunnyside Inn

1890's photo via Chicagology

'The grand opening was on a Wednesday evening in December, 1866 and reporters from the major Chicago papers were brought to the gala affair in a huge four-horse sleigh. Hyman declared to all,

“I would like you gentlemen of the press to understand that this affair will be straight to the wink of an eyelash. All the ladies are here on their honor, and Mrs. Hyman will see to it that nothing unseemly takes place.”' - excerpt from a site called Chicagology

The talk was that the establishment use for prostitution.

located on Grace Street & the then existing lakefront

The old Huntley House renamed Lake View House by 1854

The Lake View House owned by Elisha Huntley and co-managed James Rees and then co-owned to be used not only as a resort but a meeting place to discuss real estate, particularly Mr. Huntley's holdings in the old community of Pine Grove beginning in 1853 until 1890-ish. I have a open petition to the 46th Chicago ward office to create a landmark status of the current garden space that will memorialize this hotel of old Lake View. This was accomplished in 2016 with the assistance of the caretaker of community garden, the alderman, and The Ravenswood-Lake View Historical Association.

image - John Falk via Chicagopedia-Facebook

from a book called 'Chicago and It's Makers'

The caption highlights what was once 'Wright's Grove' around the Diversey Parkway area

The Depiction from above

A German Saengerfest (singing festival) was the event.

"Chicago became the festival city for the second time when the twenty-second great Saengerfest of the North American Saengerbund was held here in 1881. For weeks and months ahead, preparations were enthusiastically pushed, and the festival committee, under the guidance of the festival president, Louis Wahl, did everything in its power to insure the success of the event. When the first festival day, June 29, finally arrived, the out-of-town guests were first of all taken by the reception committee to their quarters, where they received an excellent meal for thirty-five cents."

An Article of the Event

At the corner edge of the old Lake View

Western Avenue & Devon in 1913

photo - Jerri Walker via Forgotten Chicago on Facebook

Bowmansville on Devon Avenue east of Western Avenue in 1914

photo - Jerri Walker - Forgotten Chicago on Facebook

Chicago River north at Lawrence Street Bridge 1909

via Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago

photo - Friends of Cuneo-Facebook

The turn of track known at the time as the North Western Elevated (Redline) that is now West Sheridan Road and Irving Park Road

Leland Avenue looking west 1891

Leland Avenue near Dover Street 1891

Looking west from Seeley Avenue towards Western Avenue 1890's

Sam Brown Real Estate Office

advertising the Sheridan Drive Subdivision

that was located at Clark and Wilson 1891

Sunnyside Avenue looking west for that street

Wilson and Evanston (Broadway) Avenue prior to the construction of the elevated tracks in 1907 with a

Wilson Avenue looking northwest on Malden Street 1891

Wilson and Magnolia 1891

Wilson Avenue at Malden and Magnolia

Note: these photos are from Sulzer Regional Library and are gathered and stored by the Ravenswood - Lake View Historical Association that is housed in this particular library

the corner of the former township/city

from a section of a book called Chicago: growing metropolis

photo below - Calumet 412

Montrose Avenue looking west toward Ravenswood Avenue in 1905 years before the elevated tracks would be constructed

Post Notes:

West of Western Avenue

And the Bridges that Connect the Landmasses

Forty miles north of downtown Chicago, the Chicago River

begins its journey in Park City, Illinois, where a small storm-water channel

enters the Greenbelt Forest Preserve and forms the headwaters of the Skokie

River, according to The Friends of the Chicago River. In suburban Niles the river enters

a different phase called the Upper North Branch that continues until Wolf Point

in Chicago. In this segment of my blog I will highlight the bridges that

connected the landmasses of each side the North Branch of the Chicago River

that influenced development near old Lake View. Those bridges are on the streets of Montrose,

Irving Park Road, Addison, Belmont, and (Fullerton Avenue-once the border between

Chicago & Township/City of Lake View).

the X marks the bridge crossings at this time

After a severe storm in 1885 caused the river to empty

large amounts of sewage-polluted water into Lake Michigan, plans were begun to

reverse its flow through the construction of a canal, which was completed in

1900. [The only mayor of the City of Lake View William Boldenweck was the Drainage

Broad president during this period of time.] The river now flows inland—through

the south branch and into the Illinois Waterway (Chicago Sanitary and Ship

Canal and the Des Plaines and Illinois rivers) to connect with the Mississippi

River. The reversal of the river’s flow is considered one of the greatest feats

of modern engineering. The south branch of the river was straightened between

1928 and 1930, which moved the river 0.25 mile (0.4 km) west, according to the Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Chicago River north

of Montrose Avenue

I begin with ...

Before the first bridge at Fullerton Avenue could be

built, the street had to be extended from Ashland Avenue to the river. The municipalities of Chicago and the

[Township of] Lake View both contributed to construction costs 3/4 and 1/4

respectively. [Both Chicago & Lake View bordered on Fullerton Avenue.] The

bridge opened in 1874. It was a fixed

iron bridge. It was 225 feet long and 20

feet wide. Construction costs were $5,000. The bridge was removed in 1877. The

second bridge at Fullerton Avenue was a wood and iron hand operated swing

structure. According to Chicago

Architecture Center website Swing Bridges were set up like a spinner in a board

game, which resulted in ships crashing into them, and vehicle collisions on

them were common. It was funded with contributions from [City of]Chicago (2/3)

and [Township of]Lake View (1/3).

Construction costs were $7,444. The original bridge was removed in 1894-5 [five years after the annexation of the

City of Lake View to Chicago in 1889.]

[As of 2018 this bridge was on its 4th

design.]

In 1875 when the first Belmont Avenue Bridge was built. On

both sides of the North Branch of the Chicago River at Belmont were the [townships

of] Lake View on the east and Jefferson on the west. The Belmont Avenue Bridge

was an iron fixed bridge. It was 77 feet

long and 17 feet wide. It was designed and constructed by the King Bridge

Company. Total constructed costs were $3290. Three governmental entities shared

in the costs; Jefferson ($1,491), Lake View ($1,097), and Cook County ( $694).

This bridge was a 77-foot-long and 19 feet wide bridge. In 1889, the city of Chicago annexed [the

City of]Lake View and [the Township of]Jefferson and took over ownership of the

bridge. The bridge was removed in 1893. [As of 2018 this bridge is on its 4th design.]

photo - Bridge Hunter.com

via Connecting the Windy City

The first bridge opened September 1896 [when Lake

View was a still a relatively new ‘district’ of Chicago and seven

years after the annexation of the City of Lake View in 1889.] It was 184 feet

long and 35 feet wide. It was a steel-hand operated swing bridge.

1902 photo - Ravenswood-Lake View Community Collection

map - Ebay

Designer is apparently unknown. The Superstructure Contractor was Lassing

Bridge and Iron Company [originally a Township/City of Lake View business.] The Substructure Contractor was Lydon and Drews Company. The cost was $31,345. [As of

2018 this bridge was on its 2nd design.]

The Other Bridges Mentioned

The Irving Park Road

Bridge

1903 photo - Ravenswood-Lake View Community Collection

zoomed below

Bridge

(no photo found)

Built in 1902, the bridge features three through girder spans, set onto stone and steel substructures. It appears that little alterations have been made to the bridge. The approach girders are officially listed as A-Girders by the railroad documents. The Montrose Avenue

Bridge

photo - Ravenswood-Lake View Community Collection

Working

Along the River

a 1887 view from Fullerton to Belmont

1887 map - Historical Informational Gatherers

with a zoomed view from Fullerton to Wellington

An industrial area developed along the north branch of the Chicago River from Fullerton to Diversey what today would be called today as an Industrial Park. Manufacturing was the norm in this country and in the Chicagoland area. Locating a business near a river or railroad tracks was the main means of transport for their customers in the region until better roads rails entered the scene. Notable manufacturers along this river area were the following: William Deering & Company - later to be called International Harvester/Deering Works, Northwestern Terra Cotta Company, Illinois Malleable Iron Works employing thousands of workers.

A 1894 map below of the manufacturers

the lines in this map indicate railroad tracks and the blue line indicated the North Branch of the Chicago River

The Importance of the River

in 1904

"The question of the houseboats’ legality was about as

murky as the river water. When the squatters’ camp started growing during the

‘20's, the city’s Sanitary District tried to evict the occupants, citing water

pollution and navigation concerns. When a judge issued an injunction preventing

the houseboats from being ousted in 1930, the colony grew. The Sanitary

District of Chicago had by then completed its channelization project along the

north branch which connected to the North Shore Channel."

a 1905 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map and

a 1916 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map

It opened on July 2, 1904 as the German Sharpshooter

Park, at the intersection of Belmont and Western Avenues. Targets [for shooting] were set up

on an island in the north branch of the Chicago River, when deer roamed its' woods. But wives and children complained they had nothing to do while the men

hunted; so two years later, the owners commissioned a carousel consisting of five-row wooden carousel with 70 [wooden] horses handcrafted by Swiss and Italian

woodcarvers from the Philadelphia Toboggan Coaster Company according to WTTW.

a vintage postcard of the park along the river - Ebay

When Chicagoans were Talking Secession

by Neil Gale

The What If

Chicago history

based on conditions that existed between

1910 and 1925

'There was a time when downstate Illinois controlled the

state which was not to Chicago’s advantage. Throughout Illinois history parts

of Illinois have threatened or planned to secede from the state of Illinois,

mainly because of the Chicago area being too dominant. However according to Chicago’s

history, the city once proposed to secede from Illinois to form the

"State of Chicago." On June 27, 1925, Chicagoans were talking

secession. Maybe Chicago should break off from Illinois and form a new state.

The Illinois Constitution was being violated. Every ten

years, following the federal census, the legislative districts were supposed to

be redrawn. That hadn’t been done since 1901. Downstaters controlled the state

legislature. Letting Chicago have more seats would take away their power. So

the legislature had simply refused to redistrict after the 1910 census. They

had again refused after the 1920 census. Chicago’s population had grown from

2,.2 million to 2.7 million during that time.

According to Alderman John Toman, the city deserved five

more state senators and fifteen more state representatives. So, Toman offered a

resolution to the city council—that the city’s lawyer should investigate how

Chicago might secede from Illinois. The resolution passed unanimously.

Obviously, there were going to be problems. The U.S.

Constitution specifically stated that no new state could be carved from part of

an existing state unless the existing state approves it. Would downstate be

willing to let Chicago go, and lose all that tax revenue? Probably not. But

perhaps sometime in the future. Besides, there were ways of getting around the

Constitution. Kentucky was a part of Virginia in 1792, Maine was a part of

Massachusetts in 1820, and West Virginia was a part of Virginia in 1863 during

the Civil War.

The proposed 'State of Chicago' would take in all of Cook

County. Suburbia was tiny in 1925. Out of 3 million people in the county, about

2.7 lived within the Chicago city limits. The secessionists said they’d

consider including DuPage and Lake counties, too.

Most Chicagoans seemed to like the idea of being a

separate state. Along with being freed from the downstate dictators, Chicago

would enjoy more clout on the national stage. The new state would rank 11th out

of 49 in population.

Even if the plan didn’t become a reality, the threat was

worth making. “Chicago is having trouble getting a square deal from the state,”

a South Side electrician said. “I believe the only way to get back at them is

to rebel. That would give them something to think about.”

During the 1960s, the U.S. Supreme Court’s various “one

man, one vote” rulings gave the city its fair share of legislature seats so

Chicago no longer saw the need to become its own state and the plan to leave

Illinois became part of Chicago’s forgotten history.'

Please continue to my next post called

Cultural Influencers of Lake View

Important Note:

These posts are exclusively used for educational purposes. I do not wish to gain monetary profit from this blog nor should anyone else without permission for the original source - thanks!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)